The icon of Our Lady of Philermos

The icon of Our Lady of Philermos

The icon of Our Lady of Philermos

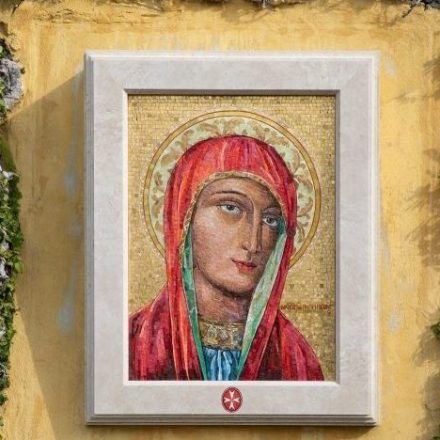

The icon of Our Lady of Philermos is, more than any other, the most sacred representation to which, for centuries, the Knights of the Order of Malta have been devoted. It is the symbol par excellence of the Marian spirituality of the ancient Order of the Hospitallers of St. John. However, Our Lady of Philermos could also be worthy of the name of patron saint of travellers, without wishing in any way to detract from the official holder of this title, St. Christopher. Few religious pictures have travelled as much and as adventurously as this small but precious portrait.

EVERYTHING ABOUT HER SPEAKS OF PILGRIMAGE

Even just to admire this face, which releases a deeply holy sense, one has to travel, taking a long journey to the National Museum of Art of Montenegro in Cetinje, where it has been kept since the Second World War. And when the icon reappeared, at the end of the 20th century, having been thought to be lost, it was welcomed like a long lost friend or, better yet, a much-loved mother from whom you’ve heard nothing for years and who suddenly shows hope when all hope had been lost.

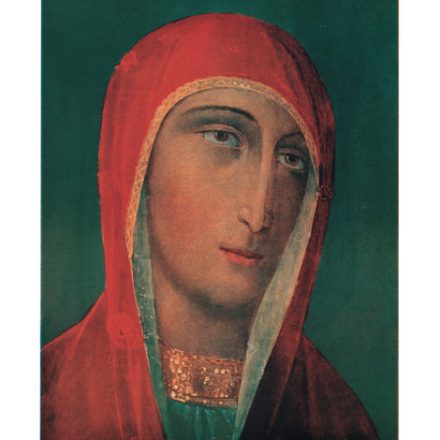

However, the dimension of the journey/pilgrimage is just one of the fascinating aspects of this little masterpiece. What is even more extraordinary is the story Theotokos Phileremou, the Mother of God of Philermo. Starting from the mystery of its origins. Could it really be the work of Luke the Evangelist as tradition says?

ITS HISTORY ACCORDING TO TRADITION

The first account, reported in the Complete calendar of Russian saints and brief miraculous news on the Mother of God, leaves no room for doubt: “According to tradition, the Hodigitria (she who leads) Filermskaia was painted by St Luke and consecrated with the blessing of the Mother of God. In around the year 46, it was taken to Antioch, the birthplace of St. Luke, and then to Jerusalem. Towards the year 430, it was taken to the church of Blacherne in Constantinople. In 626, it saved Constantinople from the Persians (…) In 1204 it was taken by the Latin army, transferred to Palestine and from there to the island of Malta”.

Another description, reported in a text dating back to the 17th century, also makes reference to the same presumed artist: “Said to have been painted by the Evangelist, Luke”. Then it makes less precise historical references. The icon, according to what is written, is supposed to have been taken to Rhodes from Jerusalem “when the island was still under the rule of the Eastern Emperors”. The timing is less certain because, apart from the invasions by the Persians in 620 and the Arabs (633-665), Rhodes was ruled, at least in name, by the Eastern Emperors until the island was occupied by the Hospitallers in 1306.

A third version appears in a Magistral Bull of the Hospitallers Order dated 1497. It states that, according to local tradition, the icon is said to have arrived in Rhodes by way of a miracle: floating on the sea, at the time of Emperor Leon the Heretic (717-741).

A LONG PILGRIMAGE

Stories aside, more precise information indicates that the portrait was housed on Mount Phileremos in Rhodes between 1306 and 1310. Even on the small Mediterranean island, its pilgrimages were constant. As written in 1594 by Giacomo Bosio, author of texts on the saints and blessed of the Order, “the highlight devout picture” was moved within the walls every time danger arose: an example of such movement occurred when the Turkish army was about to lay siege to the island of Rhodes in 1480. Then, after having spent time in St. Catherine’s Church, it returned to the mountain, taking a journey of about 10 miles.

From Rhodes to Malta

The invasion by the troops of the Sultan Suleiman between 1522 and 1523, led to the loss of the island by the Knights. The exiled Grand Master, Fra’ Philipe Villiers de l’Isle Adam, was allowed to take the Order’s most venerated and previous reliquaries with him: the right hand of St. John the Baptist, a fragment of the authentic Cross and, of course, the icon of Our Lady of Philermos, which set out on this new pilgrimage accompanied by a standard bearing the words: «Afflictis tu spes unica rebus», “You are the only hope in all affliction”.

These travels brought the religious picture to Italy. First to Messina then to Naples, where it was carried in a procession during the plague of 1523. Then it was the turn of Civitavecchia and Viterbo, where it remained three years, from 1524 to 1527, in the Church of Saints Faustino and Giovita, which houses a painting of the Virgin, donated by the Knights and still venerated under the name of Madonna of Constantinople.

But this was by no means the end of the journey. After spending time in Nice and Villefranche, the icon was taken to Malta in 1530, housed in the Church of San Lorenzo in Birgu, the “victorious city” not far from Fort St. Angelo. And here there’s another legend, also recounted by Giacomo Bosio. During the Great Siege of 1565, which ended with the victory of the Knights “a pure white dove was seen to rest on the miraculous icon of Our Lady of Philermos; it stayed there for hours; hence the people were given a sign that they would soon be freed from the siege”. After a short stay in Our Lady of Victories Church in Valletta (1571-1578), the icon was housed in the St. John co-cathedral of the Maltese capital. Here it stayed for more than two centuries, enhanced with jewels, clothes and furnishings. Other movements were on their way though.

From Malta to Saint Petersburg

In 1798 General Bonaparte occupied the island of Malta. He forces the Knights to abandon the island and ordered that all churches and palaces to be stripped of everything valuable, including the rich ornaments of Our Lady of Philermos. However, the icon was saved by the Grand Master Fra’ Ferdinand von Hompesch, along with two other reliquaries. It then arrived in Trieste, staying just a year. In 1799 it was consigned to Tsar Paul I, the Order’s new Grand Master, through Balì Giulio Litta. It was welcomed to Gàtchina, near St. Petersburg, and, by express order of the Tsar, covered with a riza, the characteristic metal covering of icons, made entirely of gold and decorated with jewels: only the face remained visible.

The pilgrimages however continued. From Gàtchina, the icon was transported to the Imperial Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, where it remained until 1917. From here – destiny of the tireless traveller – it was taken regularly to Gàtchina for a few days, for celebrations and ceremonies.

From Russia to Yugoslavia

When the Bolshevik revolution exploded, in 1917, the Icon, along with other reliquaries, arrived at the Kremlin in Moscow. Then it returned to Gàtchina. It didn’t stay there long, travelling initially to Reval, in Estonia, and then to Copenhagen, where it was given to Maria Feodorovna, the mother of the Tsar, who had taken refuge in Denmark and who, in 1928, shortly before her death, entrusted it to her daughters. They consigned it to the Synod of the Bishops of the Russian-Orthodox Church outside of Russia. For safekeeping, the Bishops kept it in Berlin first of all, and then gave it to King Alexander I of Yugoslavia, who took it to Belgrade, to the Royal Palace of Dedinje. During the German bombings of 1941, it was to mysteriously disappear from this location.

The Order of Malta went to work. In 1942, Grand Master Fra’ Ludovico Chigi Albani received word that the icon was possibly in the monastery of Ostrog, in Montenegro. However, a special inspection ordered by the Italian governor, Pirzio Biroli, had a negative outcome: the portrait was probably hidden elsewhere.

ITS REPRODUCTIONS

During the Italian occupation of Rhodes, the government in Rome had asked Russia to return the icon in order to restore the ancient worship on Mount Phileremos. But Moscow could not trace the original and, in 1925, sent a copy, probably commissioned by Tsar Nicolas I in around 1852. This was welcomed into the reconstructed sanctuary on Mount Phileremos, entrusted to the Franciscan monks of Assisi. Another copy, made in 1931 by the Italian artist Carlo Cane and modelled on the Russian copy, set in a frame bearing the inscription “Ave Maria”, went to St. John’s Cathedral, also in Rhodes. The copies too, however, were destined to travel like the original. The “Italian” copy was transferred at a later date to the chapter house on Mount Phileremos, where it can still be found today. The “Russian” version however when Rhodes was annexed to Greece in 1948 was brought to the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Assisi (Italy). Here at the beginning of September, members of the Order meet in pilgrimage.

ITS REDISCOVERY

But what had happened to the original? It was found thanks to the insistence of an Italian scholar Giovannella Berté Ferraris di Celle. She had written a book on the icon in 1988, but her interest didn’t stop there: she continued with her search. She had heard rumours in the religious and monastic environments, particularly those of the Orthodox Church, according to which the great reliquaries of Malta and the icon had not been destroyed, but were located in a monastery in the south of what was then Yugoslavia. After writing numerous letters and continuing to insist, she finally received a reply from the Metropolitan of Belgrade: yes, the icon was in Cetinje in Montenegro! And so it was that, in May 1997, the tenacious researcher completed her work: “I was moved by being able to worship this holy icon”. Several years later, between the 12th and 15th of March 2004, the Grand Master of the Order of Malta, Fra’ Andrew Bertie led the pilgrimage to the icon. Followed by a delegation of the Order, he paid devout homage also to the other two holy reliquaries of the Order: the authentic Cross and the hand of St. John the Baptist, kept in the Orthodox monastery of the Nativity.

An icon with an extraordinary history, still today a symbol of the Order of Malta’s Marian spirituality and emblem of its history. The members of the Order of Malta – as their predecessors have done over the centuries – continue to pray and to invoke her as their protector and to refer to her in the most difficult moments. On 8 September they celebrate her feast all over the world.